Chalmers Advanced Python

Lecture Notes for the Continuation Course in Python

Aarne Ranta, John J. Camilleri, Muhammad Mustafa Hassan

Preface

This guide is written for the students of the continuation course in Python at Chalmers University of Technology and University of Gothenburg. The original name of the course was “Advanced Programming in Python”, starting in 2021. As of 2024, the course name is “Continuation Course in Programming in Python”, which reflects better its character as an intermediate rather than an advanced course.

The purpose of this guide is to give a unified view of the course and help your learning by showing the big picture and pointing you to further reading. It is not a complete description of the course material: we found it unnecessary, and even harmful, to repeat and digest all the material that you are expected to read. On the advanced level of programming, you should be able to read the original documentation, which you can find on the internet, and which may be difficult or even confusing. This guide will help you to get started, by giving pointers to material that we found relevant and which you at least should read while studying this course.

Table of contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Learning the Python language

- 3. Diving into the official tutorial

- 3.1. Tutorial 1: Whetting your appetite

- 3.2. Tutorial 2: Using the Python interpreter

- 3.3. Tutorial 3: An informal introduction to Python

- 3.4. Tutorial 4: More control flow tools

- 3.5. Tutorial 5: Data structures

- 3.6. Tutorial 6: Modules

- 3.7. Tutorial 7: Input and Output

- 3.8. Tutorial 8: Errors and Exceptions

- 3.9. Tutorial 9: Classes

- 3.10. Tutorial 10 and 11: the Standard Library

- 3.11. Tutorial 12: Packages and virtual environments

- 3.12. Tutorial 13: What Now?

- 4. Storing and retrieving information

- 5. Graphs and graph algorithms

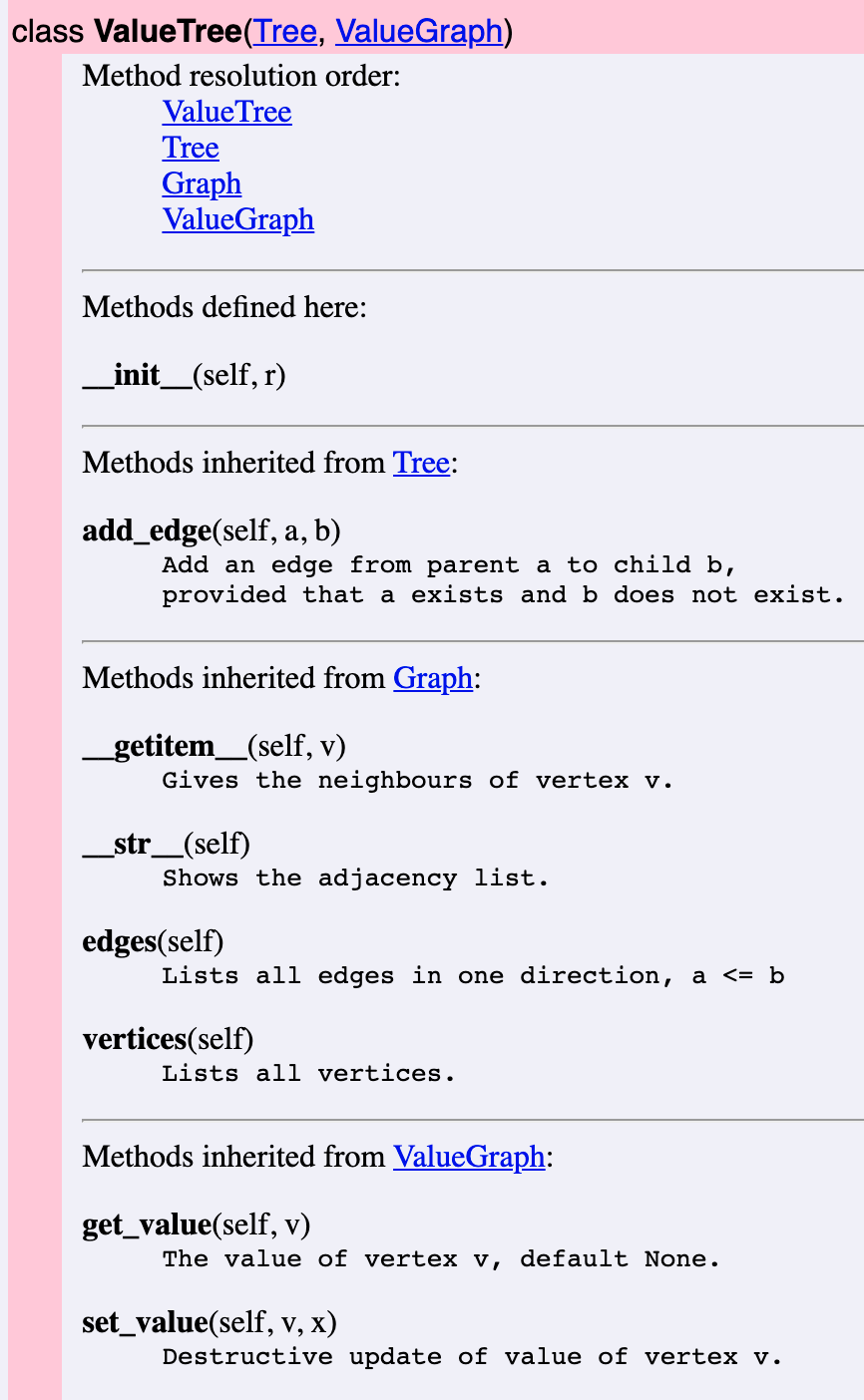

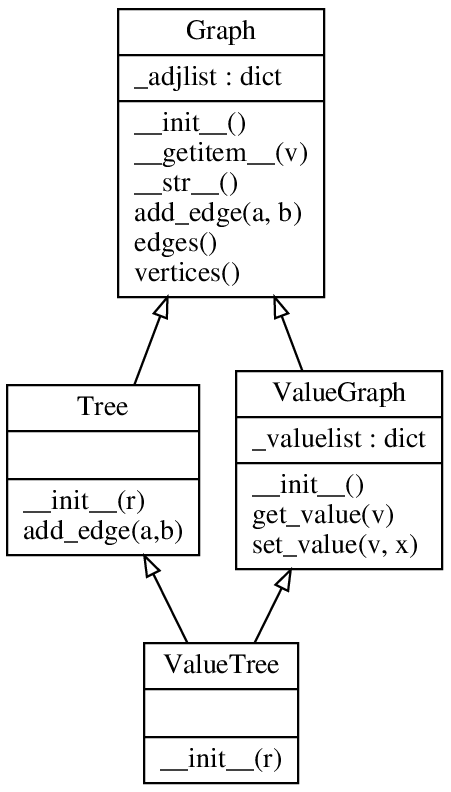

- 6. Object-oriented design

- 7. Testing

- 8. Visualization

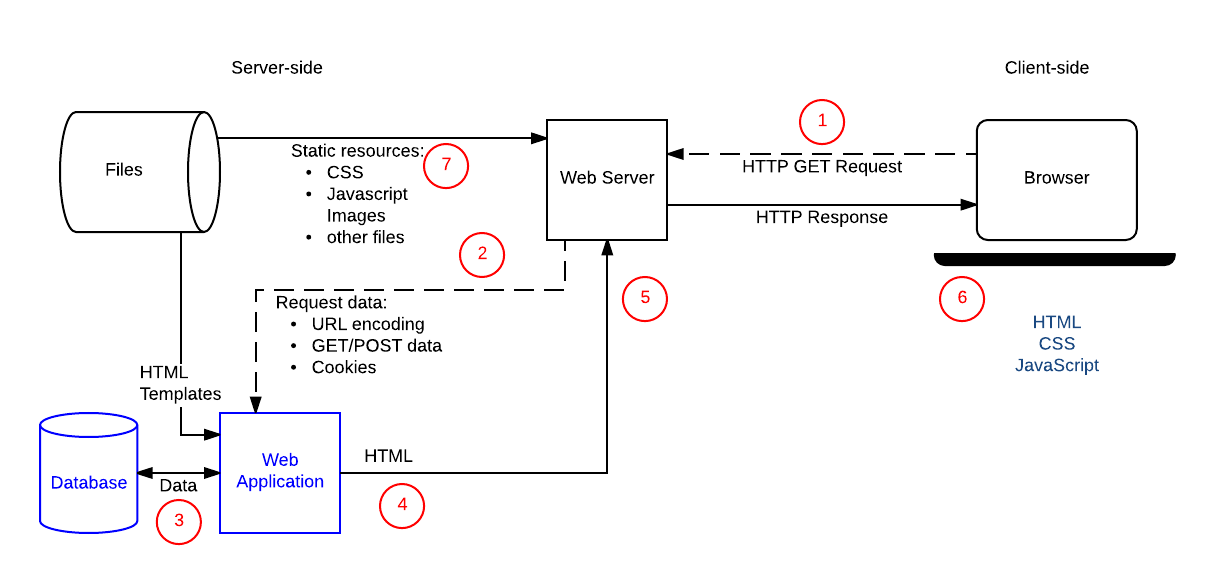

- 9. Web programming

- 10. The rest of Python

- A. Appendix: Git version control system

1. Introduction

1.1. The aims of this guide and the course

This course is a second course in programming, after an introduction course. After learning the basics of programming, the ambition here is to reach a level of completeness:

- Complete knowledge of Python: you will know all constructs of the Python language, not only the ones covered by introduction courses.

- Universal programming potential: you will get the confidence that you can solve any programming task, as just a matter of having enough time to study the problem and work on it.

The latter goal is related to the idea of a computer as a universal machine, which is able to perform all tasks that an algorithm can do. What is needed for this is, in addition to the peripheral devices, a programmer that can implement those algorithms on the machine. The goal of this course is to help you to become that programmer.

Really to become an advanced programmer, you will also need to learn some other things. This includes courses that are more specific than just programming: they will cover topics such as data structures and algorithms, machine learning, and software engineering. Even more importantly, you will have to develop your skills by programming in practice. Another name for the “universal programmer” is full-stack developer. This means a programmer that masters all levels of a practical application. The term is often used more specifically to mean a web application consisting of a back end, database, and a front end. This course is centered around a programming project where you will build a full-stack web an application.

1.2. Programmers of different kinds

This course is mainly targeted to bachelor-level students, who have studied an introductory Python course. But it was originally designed, and is still available for, students from different backgrounds - computer science, data science, mathematics, physics, chemistry, design, engineering, business, ecology - and levels - bachelor, masters, PhD. Many of the mentioned fields have their own cultures of programming. It is helpful to identify some of them, because you are likely to meet these cultures during your future programmer career. The following three profiles are of course caricatures, but you can easily find code examples that satisfy all characteristics in each of them.

1.2.1. The Computer Scientist

This is the context in which the course is formally given. In this context, programming is a branch evolved from applied mathematics. The programmer is interested in the mathematical structure of programs and tries to find the most elegant data structures and algorithms. She also wants to make them as general and abstract as possible. Her programs are typically not solutions to practical problems, but more on the level of libraries that can be used by others who are solving practical problems. The hard-core computer scientist programmer does not primarily use libraries herself - instead, she tries to understand and build everything from the first principles.

Here are some typical features of the Computer Scientist’s programs:

- they consist of functions whose size is just a few lines each,

- each function has a clear mathematical description,

- they are often close to pseudocode that could be published in a textbook,

- variable and function names are often short and similar to ones used in mathematics,

- the code avoids language-specific idioms,

- classes are used mainly to define data structures - not to structure entire programs,

- the code is accompanied by arguments about correctness and complexity,

- the code is not tested thoroughly, just demoed with a couple of examples if not proved correct,

- there are very few comments in the code, since it is aimed to be self-explanatory,

- the programs are written by single persons and are self-contained.

With the growing needs of computer programs, Computer Scientist programmers are becoming more and more of a minority. They have, to some extent, made themselves superfluous by creating libraries that other programmers can rely on and do not need to understand the internals of. But of course, they are needed in the front line of research to invent new algorithms, new programming languages, and new kinds of computing devices. It is also common that theoretical Computer Science questions are used in interviews at tech companies.

1.2.2. The Software Engineer

This category contains the majority of programmers who have programming as their profession. They typically have a Computer Science background, but have “grown up” from that when getting encountered with the “real world”. They have learned several programming languages and have lots of algorithms and data structures in their “toolbox”. At the same time they know that, to solve a practical problem or to create end-user software, no single technique is sufficient in itself. They have no time to go into the internals of algorithms, but use whatever libraries and tools they - or their managers - have learned to trust. They often work in large groups and try to maintain a level of readability that enables others in the group take over their code.

Here are some typical features of the Software Engineer’s programs:

- they are divided into modules and classes with complex hierarchies,

- each unit of the program is documented in detail with comments and often with diagrams,

- the names of variables, functions, and classes are long, descriptive, and systematic,

- the code is accompanied by a comprehensive set of tests,

- the code uses libraries whenever possible, avoiding to “reinvent the wheel”,

- the code has a long lifetime and may have ancient layers that no-one dares to touch any more,

- the full software system may have code written in many languages and typically also contains configuration files and build scripts.

Competent software engineers on different domains of application are constantly and increasingly wanted by employers. Their competence may be based on academic education, but it is primarily a product of years of experience. It is not proven by academic degrees or publications, but by a portfolio of software that the programmer has designed or contributed to. This experience often comes from enterprises, but it can also be built in open source projects where the programmer has made major contributions.

1.2.3. The Occasional Programmer

This is the category of programmers with no or little training in Computer Science. They can be teenagers or other hobby programmers, but also proficient scientist or engineers in other disciplines, who see programming as something that can be learned in an afternoon or two, when it is needed for some computations or experiments. For scientists, programming is a replacement of the earlier use of pencil and paper for similar tasks (now decades ago). Computers make it faster to apply mathematical formulas, and they make it feasible to deal with larger amounts of data than in earlier times, in particular if statistics or machine learning is involved.

Typical features of programs in this category are:

- the structure of the code is simple and linear - in Python, this means that it consists of top-level statements and global variables, avoiding functions and classes,

- the program is a single file that can be thousands of lines long,

- variable names are short and unsystematic,

- input and output is performed freely in different places of the code,

- as there are no return statements, the only way to combine the code with other programs is to pipe its output to them as a string,

- the code uses freely whatever libraries seem to do the job,

- libraries are often imported in the middle of the file rather than in the beginning,

- the code is written by one person and is not intended even to be read by others,

- the code does one thing, aiming to do it with as little effort as possible,

- the code is only run once or a few times,

- well, it is often run with the same input a large number of times, until it seems to do the job in the expected way,

- if a related task appeared again, the code is copied and patched to fit for that purpose.

This category of programmers is probably the largest, and includes both professionals and hobby programmers. In fact, since Python supports this style so well, it is occasionally used by all kinds of programmers. Programs in this category are often called scripts rather than “real programs”. If you search the web for a Python solution to a particular problem, you are likely to find several examples of this kind of code: scripts with linear structure where large blocks are copies of each other and where input and output happen all over the place.

1.2.4. Programming in this course

The main part of this course belongs to the Software Engineer category:

- we want to solve substantial practical problems,

- we use proven techniques and libraries for this,

- we structure the code in a clear and reusable way,

- we document the code in a way that explains it to other programmers,

- we raise the level of reliability of the code by systematic testing.

As a support for this, we will also look into some Computer Science topics:

- the data model and semantics of Python,

- some fundamental algorithms and their theoretical aspects.

We will neither cover nor recommend the Occasional Programmer’s style, not even for highly competent professionals in advanced scientific fields. If you are a scientist, you are probably right if you think that programming is easy compared with the deeper questions you deal with in your actual research. But even then, we believe that it is helpful to learn about the algorithms and data structures of the computer scientist, as well as the techniques and practices of the software engineer. This can make you both faster and more confident when writing code for your next experiment.

One can also compare programming with other hobbies: almost anyone can learn to cook food or play an instrument without any formal training or even without reading books that teach these skills. But if you take your hobby seriously, it will give you more satisfaction if you know that you are doing it “the right way”.

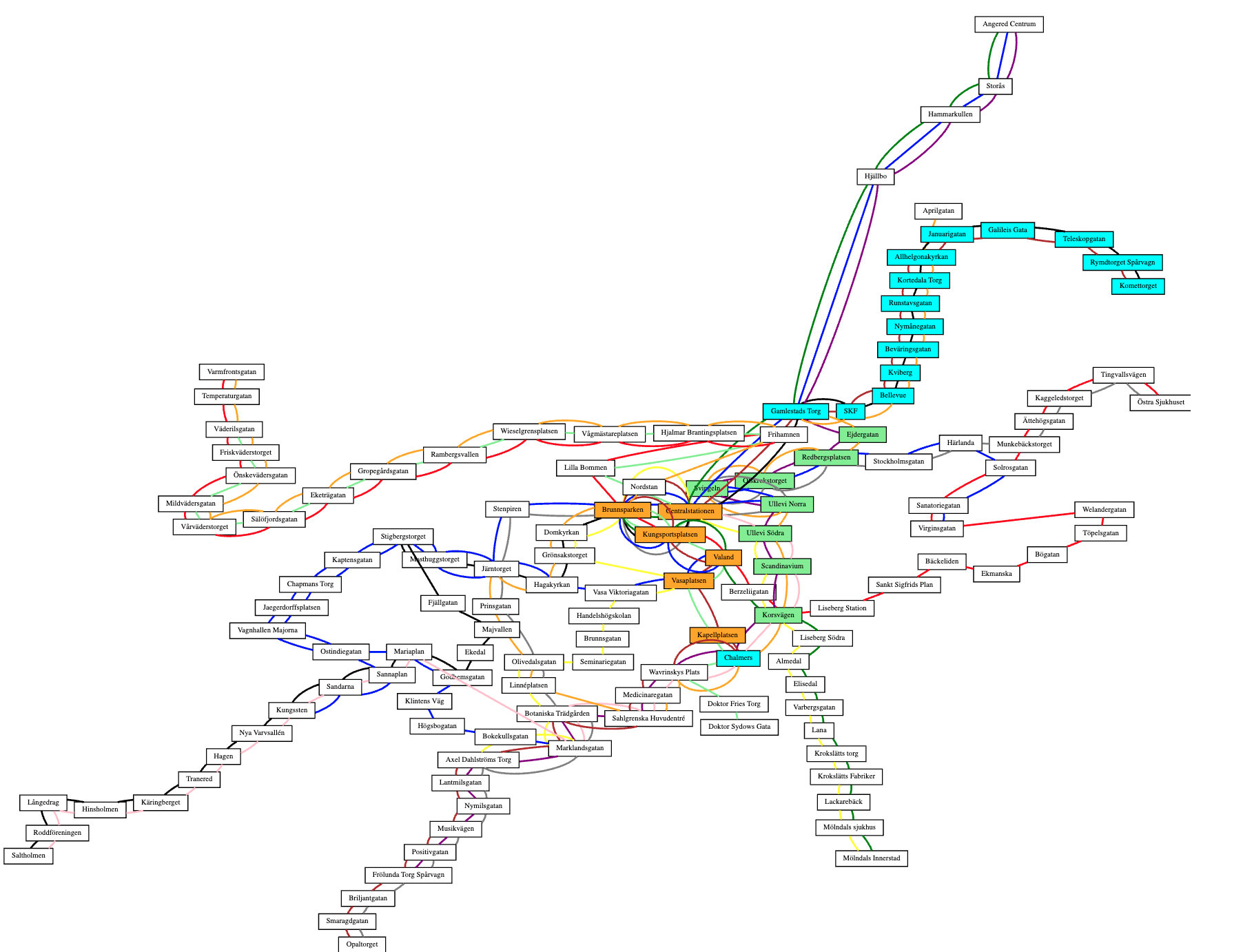

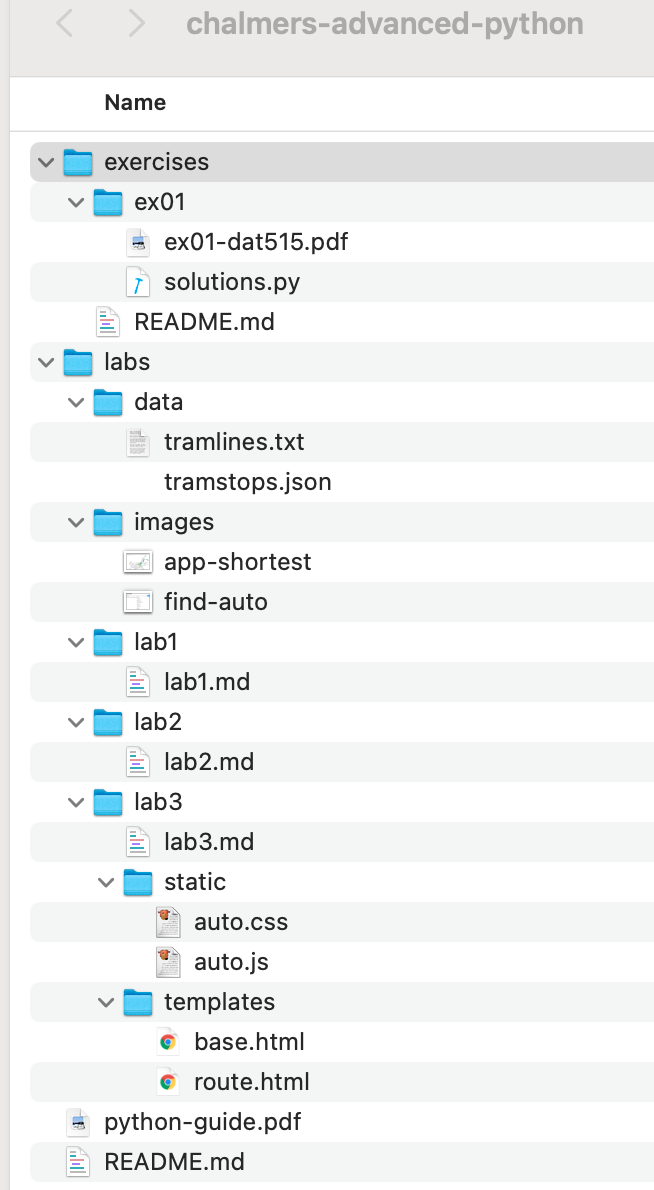

1.3. The Lab

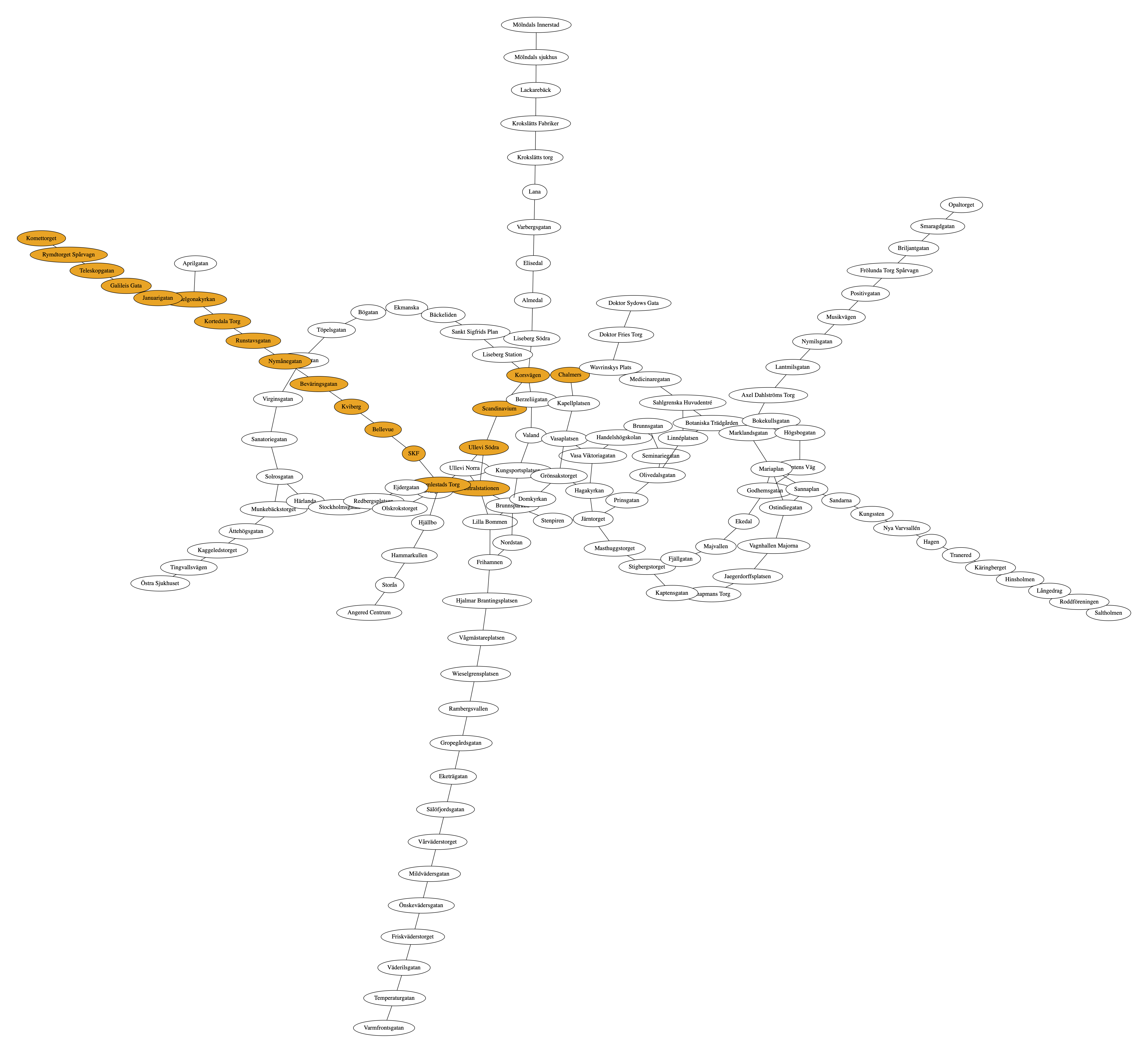

Much of the course is centered around the Lab, a programming assignment whose goal is to build a “full-stack” web application. In the final demonstration of the application, the user can search for a route in the Gothenburg tram network and get it drawn on a map - in the way familiar from the numerous travel planning applications on the web. The Lab is described in detail in three parts (Lab 1, Lab 2, and Lab 3) so let us here just explain the purpose of the lab in the context of the course.

The Lab is primarily an exercise in practical Software Engineering and serves the following learning outcomes:

- to write modular, well structured programs with reusable components,

- to use standard libraries and understand their documentation,

- to apply testing and version control practices,

- to read and peer review code written by others,

- to document program code so that it can be understood by others,

- to get the basics of some useful techniques (graphs, visualization, web programming) that can be applied to numerous other tasks.

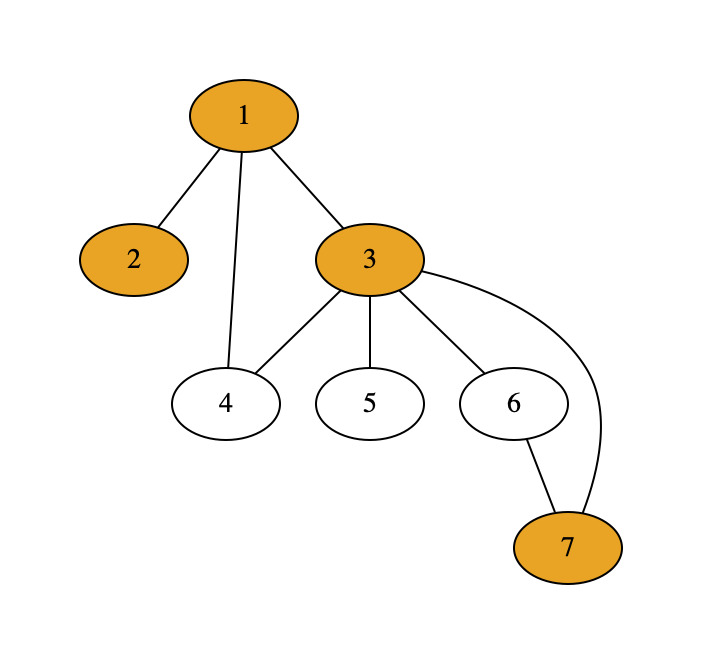

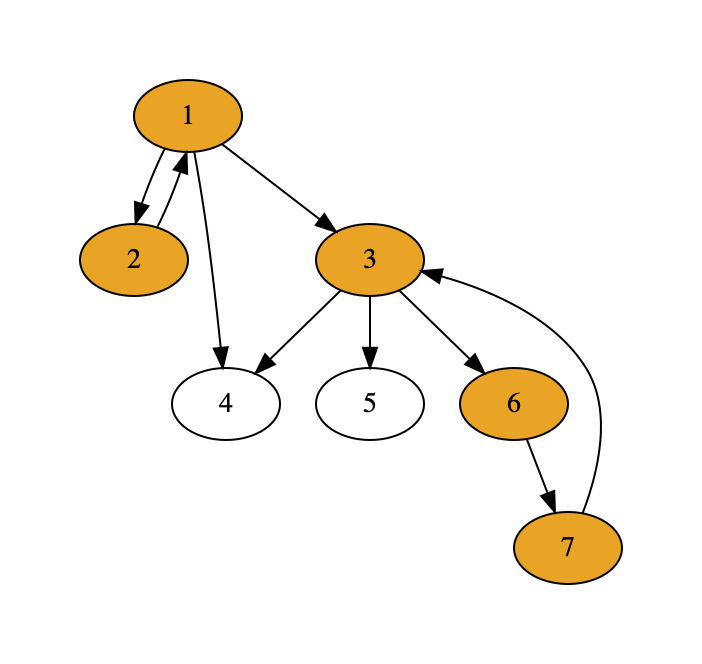

In addition, the Lab has some Computer Science aspects:

- to learn about graphs, which are a fundamental concept in many computing tasks,

- to widen your imagination so that you can search for solutions to practical problems from well-known general algorithms.

The title page of this document shows a screen dump of the final web application.

The standard Lab was in earlier course instances extended with a couple of related tasks, which use graphs for other things than route finding. They can be found in the “old-labs” directory of the course repository, in case you want to try your hand with them:

- map colouring: making sure that neighbouring countries have different colours,

- machine learning: finding clusters (tightly connected parts) in a network.

The basic lab is estimated to require up to two weeks of working time in total. The actual time consumption is individual and depends greatly on your previous experience.

2. Learning the Python language

One goal of the course is to bring you to a level where they have seen “all of Python”. This does not yet mean that you can use all constructs of Python efficiently. But you will have at least heard about things like dictionaries, slicing, comprehensions, decorators, inheritance, dunder methods, and other special constructs that might not be familiar from your previous programming language.

2.1. What do I learn when I learn a language

Computer scientists and software engineers typically know several programming languages. They are also comfortable in learning new ones. Actually, if you are young (say, under 40), it is unlikely that Python will be the language of choice during the rest of your remaining professional life. Likewise, for most of us over 40 at least, Python is not our first programming language, but it can be, for instance, Java or Haskell or C or Pascal.

When learning your second or third programming language, you certainly do not need to learn everything that absolute beginners are taught their first programming language. You only need, so to say, learn the differences between the new language and your earlier ones.

The situation resembles learning a second language when you already know your native language - for instance, learning English when you already know Swedish. It has probably taken you at least seven years to learn to speak, read, and write Swedish fluently. You have had to learn not only what words mean which things, but also the very idea that words can stand for things, and that written signs can represent sounds. While learning this, your brain and motoric skills have developed to use a language. If you start learning English at this point, most of this infrastructure is already in place. Therefore, it is not uncommon to learn a new language fairly well in a couple of months, which is totally unconceivable when a child learns its first language.

So let us assume, analogously to Java programmers learning Python, that you are a native speaker of Swedish beginning to learn English. You know that the language consists of words, which are combined to phrases and sentences. What you need to learn is

- syntax: how phrases and sentences are formed,

- vocabulary: what words are used for what things.

In many cases, learning the syntax of a new language is a task that can be completed in a couple of weeks, since it will not be very different from your earlier languages. You will learn, for instance, that negation in English is formed in a different way from Swedish, by using auxiliary verbs (I don’t know instead of I know not). It might take longer to use actively all parts of the syntax, but you will at least understand the structure of what you read, even if you need to look up words in a dictionary.

The vocabulary, in contrast to syntax, involves life-long learning. Even native speakers may occasionally need to look up a word in a dictionary.

Now, when learning Python on top of Java (or any other programming language on top of any other one), it is a good idea to start with the syntax - more precisely, how its syntax differs from Java, “how negation is expressed in Python” (yes, it uses the keyword not instead of the operator !).

Most of this will be fairly obvious and follow a handful of general rules, while some things have no counterparts in Java.

At the same time, some things available in Java are not available in Python, and for those things you will have to learn to express them in a different way.

Within a week or so - Python syntax is a lot easier than English - you will be able to understand the syntactic structure of everything that is written in Python. There may be things you will never use in your own code, and will probably have a bias for Java-like expression - just like Swedish native speakers, even when fluent in English, can be biased to Swedish-like constructs.

In this course, we will actually try to help you become more Pythonic, since this will give you some satisfaction as well as credibility among Pythonistas. But I must confess that, since my own “native” programming language is not Python, I cannot guarantee always to be Pythonic myself.

What about the vocabulary of Python? There are 35 reserved words (“keywords”), and they are quickly learned as a part of the syntax. In addition, there are 68 built-in functions, many of which you will not need any time soon. But the main bulk of the vocabulary is in library functions and classes, and they involve life-long learning. The only viable approach is to learn to “look up words in the dictionary”, that is, search for class and function names in library documentation.

2.2. Some characteristics of Python syntax

2.2.1. Modules, classes, functions, statements

Assuming that your first language is Java, you have probably started with a “Hello World” program like this one:

class Hello {

public static void main(String args[]){

System.out.println("Hello World");

}

}

In order to run it, you have first compiled it to Java bytecode with the ‘javac’ program, and then executed the resulting binary with the ‘java’ program:

$ javac Hello.java

$ java Hello

Hello World

If you mechanically convert your Java program into Python code, you will get

class Hello:

def main():

print("Hello World")

Hello.main()

In order to run this, you just need to run ‘python’ (often named ‘python3’ to distinguish it from earlier versions):

$ python3 hello.py

Hello World

In other words, there is no separate step of compilation, but you can “run your program directly”. (In reality, there is a compilation phase to Python’s bytecode, but it happens behind the scenes.) Thus running the code is simpler, but the code itself is about as complicated as in Java.

However, the code shown above is what you end up with if you directly convert your Java thinking into Python. The “normal” Hello World program in Python is much simpler:

print("Hello World")

This program consists of a single statement - no class, no function is needed. There is also an intermediate way to write the same program, which contains a function but no class:

def main():

print("Hello World")

main()

If your background is in C or Haskell rather than Java, this will probably be the most natural way to write the Hello World program.

The Hello World examples illustrate the different levels in which programs are structured in both Java and Python, and also in many other languages:

- modules (typically files),

- classes,

- functions (or “methods”),

- statements,

- expressions.

In Java, these levels are strictly nested: expressions reside inside statements, statements inside functions, functions inside classes, and classes are the top-level structure of modules. In Python, the same strict hierarchy can be followed, but this is not compulsory. It is common that a top-level module is a mixture of classes, functions, and statements. An extreme case is a module consisting only of statements: this is the dominating style in what we called “occasional programming” and has given Python the label “scripting language”.

Even though we will discourage code consisting of top-level statements, we have to add that Python in fact does not even force any nesting of the levels: class and function definitions are themselves statements, and can appear anywhere inside other statements, such as the bodies of while loops.

Hence, if you want to write ten times “Hello World”, you can do it as follows:

i = 0

while i < 10:

class Hello:

def main():

print("Hello World")

Hello.main()

i += 1

This, of course, is not good use of the freedom you get in Python. It is overly complicated to write, as well as overly expensive to run (because extra code is generated under the hood every time a class or a function is defined). But we will later see situations where functions inside functions, or even classes inside functions, are a good way to write programs.

2.2.2. The layout syntax

Both Java and C programmers are used to terminating statements with semicolons (;) and enclosing blocks of code in curly brackets ({}).

This is not the case in Python (nor in Haskell).

Instead,

- statements are terminated by newlines,

- blocks are marked by adding indentation.

As a general rule,

- a line ending with a colon (

:) marks the beginning of a new block, expecting added indentation on the next line, - these lines start with a keyword such as

class,def,while, - a block ends when indentation comes back to some of the earlier levels.

A slight modification in these rules is that it is possible to divide a statement, or a line expecting a new block to start, into several lines.

In that case, one also has either to end each line but the last with a backslash \ or be inside the scope of an open parenthesis or bracket.

Thus all of the following are permitted:

x = 6 +\

7

x = (6 +

7)

xs = [6,

7]

Such examples are, however, rare and typically appear only if the lines contain expressions that are two long to fit into the recommended 79 characters per line - for example, long lists or dictionaries.

And yes, indeed, Python comes with recommended lengths for lines and indentations:

- lines should not be longer than 79 characters,

- each indentation level should be 4 spaces (no tabs recommended),

- each class and function definition should be separated by 2 blank lines.

Such rules may sound pedantic at first, but if you follow them, they will soon become a second nature and make your Python code easier to read.

2.2.3. Dynamic typing

Another thing that Python is known for is the lack of types in code:

- function definitions do not indicate argument or return types,

- variable types are not declared.

The lack of types in Python source code is sometimes taken to mean that “Python has no types”. But this is not true: Python does not have types of expressions, but it does have types of their values, i.e. objects that are created at run time, when the program is executed. Hence the correct term to use is dynamic typing.

Dynamic typing implies that there is no static type checking of your source code. An expression - such as a variable or a function call - can have different types in different places in code, and even at different runs of the program. It can then happen that no possible type is found, which leads to a run-time type error.

A statically typed language such as Java can find type errors at compile time and prevent the execution of the program. This is not provided by Python: it can in fact happen that a program is run 1000 times without failures, but after that a type error is encountered when the execution, for the first time, enters a rarely used branch of some conditional. Thus it is difficult ever to be sure that your Python program is failure-free.

What is more, the lack of static checking does not only concern types, but also function and variable names. If a name in a rare branch has a typo, making it into a name that is not in scope, you will only notice this when some run of the program enters this branch.

Some later extensions of Python have made it possible to equip functions type annotations, and there are programs that perform static type checking. This is not yet standard, but it is increasingly used, and we will introduce some of it during this course to tell the complete story of Python. Static type annotations are particularly useful in the documentation of code, especially function type signatures. But they are deemed to be incomplete, because Python is intended to support a high degree of polymorphism. This means that functions can be applied to many different types, and it is difficult to specify in advance which types these exactly are. Type information in library documentation is often - particularly in older libraries - given in natural language rather than as type annotations.

2.3. A grammar of Python

This section is something you can just glance through and use later as reference. The main purpose at this point is to show that there is not so much language-wise you need to learn: just a couple of pages. We will explain most of the things in more detail when going through the tutorial.

Our grammar is a condensed and somewhat simplified version of the official grammar in

https://docs.python.org/3/reference/grammar.html

We show the syntax of Python in the BNF notation (Backus-Naur form). While the grammar covers slightly less than the full grammar, its shortness is mainly due to its higher level of abstraction. In particular, it does not indicate precedence levels, which regulate the evaluation order and the use of parentheses.

<stm> ::= <decorator>* class <name> (<name>,*)?: <block>

| <decorator>* def <name> (<arg>,*): <block>

| import <name> <asname>?

| from <name> import <imports>

| <exp>,* = <exp>,*

| <exp> <assignop> <exp>

| for <name> in <exp>: <block>

| <exp>

| return <exp>,*

| yield <exp>,*

| if <exp>: <block> <elses>?

| while <exp>: <block>

| pass

| break

| continue

| try: <block> <except>* <elses> <finally>?

| assert <exp> ,<exp>?

| raise <name>

| with <exp> as <name>: <block>

<decorator> ::= @ <exp>

<asname> ::= as <name>

<imports> ::= * | <name>,*

<elses> ::= <elif>* else: <block>

<elif> ::= elif exp: <block>

<except> ::= except <name>: <block>

<finally> ::= finally: <block>

<block> ::= <stm> <stm>*

<exp> ::= <exp> <op> <exp>

| <name>.?<name>(<arg>,*)

| <literal>

| <name>

| ( <exp>,* )

| [ <exp>,* ]

| { <exp>,* }

| <exp>[exp]

| <exp>[<slice>,*]

| lambda <name>*: <exp>

| { <keyvalue>,* }

| ( <exp> for <name> in <exp> <cond>? )

| [ <exp> for <name> in <exp> <cond>? ]

| { <exp> for <name> in <exp> <cond>? }

| - <exp>

| not <exp>

<keyvalue> ::= <exp>: <exp>

<arg> ::= <name>

| <name> = <exp>

| *<name>

| **<name>

<cond> ::= if <exp>

<op> ::= + | - | * | ** | / | // | % | @

| == | > | >= | < | <= | !=

| in | not in | and | or

<assignop> ::= += | -= | *=

<slice> ::= <exp>? :<exp>? <step>?

<step> ::= :<exp>?

Here are the reserved words, each of which also appears in the above grammar:

and as assert break class continue def del elif else except False finally for from global import if in is lambda None not or pass raise return True try while with yield

The literals are infinite classes of “words”, the most important of which are:

-

strings: enclosed in single quotes

'...', double quotes"...", or multiple lines between groups of three quotes"""...""", -

integers: any number of digits

1234567890, -

floats: digits with decimal point and possibly with exponent indicating powers of ten

3.14,.005,2.9979e8,6.626e-34,

Comments are lines starting with #.

A comment can also terminate a non-comment line, but it is recommended to use entire lines.

Multi-line comments can be given as string literals in triple quotes """, which is also a common way to “comment out” longer pieces of code.

To conclude the explanation of words, the following built-in functions will appear throughout the course:

abs(x)absolute value of a number,bool(x)conversion from various types to booleans,chr(n)conversion from numeric code to character,dict(c?)creation of or conversion to a dictionary,dir(m)listing of contents in a module,eval(s)evaluation of a string as an expression,exec(s)execution of a string as a statement,float(x)conversion to a float,help(f)documentation of a function, class, or module,input(p='')receiving input from promptp,init(x)conversion to integer,len(c)length of a collection,list(x?)creation of or conversion to list,max(c)maximum of a collection,min(c)minimum of a collection,next(g)receive the next object from a generator,open(f)open a file,ord(c)numeric code of a character,print(x*)print a sequence of objects,range(m=0, n), range of integers frommton-1,reversed(s)reverse of a sequence,round(d, p=0), round a float topdecimals,set(c?)creation of or conversion to a set,sorted(s)sorting a sequence,str(x)conversion to a string,sum(c)sum of a collection,super()superclass of a class,tuple(c?)create or convert to a tuple,type(x)type of an object.

The tutorial will cover many of these in more detail. A full list, with full details, can be found at:

https://docs.python.org/3/library/functions.html

In addition to the built-in functions, there are several methods for built-in classes that are used all the time. Here are some:

- strings:

split(),join(),format(),index(), - lists:

append(),sort(),reverse(),pop(), - dictionaries:

get(),keys(),values(),items(), - sets:

add(),remove().

The on-line help in the Python shell is always available for more information. For instance, the command:

help(str)

gives a detailed list of all methods available for strings.

3. Diving into the official tutorial

This chapter goes through the official Python tutorial in:

https://docs.python.org/3/tutorial/index.html

by showing some highlights from it. The tutorial is written by the creator of Python, Guido van Rossum. It covers practically everything in the Python language, and does it in a way that makes you hear van Rossum’s line of thought when designing the language. Hence it is recommended reading from the beginning to the end. However, it is not a tutorial for beginner programmers, but assumes - just like we are doing here - that you already know the basic concepts from some other context.

3.1. Tutorial 1: Whetting your appetite

There is one point we want to raise: the chapter says that “Python also offers much more error checking than C”. This is not completely true, because C has static type checking and Python does not. In C - as in many other languages - static type checking is needed to support compilation to bare machine code (as opposed to virtual machine code in the case of Python). In processors such as Intel and ARM, different instructions and registers are used for different types of objects, e.g. for integers and floating point numbers. To make an optimal use of the machine, one has to know the types of expressions at compile time.

Static typing and compilation to machine code is what makes languages like C to enable more efficient programs than Python. This is because Python programs, when executed by a computer, must eventually use the machine code instructions of the computer. The execution of virtual machine code needs several times more instructions than if the same algorithm was directly available in real machine code. Much of this is, however, helped by enabling Python code to use modules written in C via a foreign code interface. Many of the standard functions and methods, e.g. for lists and dictionaries, are ultimately written in C. Using them whenever possible is therefore not only easier but also more efficient than writing your own algorithms over lists and dictionaries.

3.2. Tutorial 2: Using the Python interpreter

This chapter explains the different ways of invoking the Python interpreter. The main options are:

- running the entire program from the operating system shell (in a way familiar from Java and C),

- opening the Python shell and importing the module from there (familiar from e.g. Lisp, Haskell, and Prolog).

From the operating system shell

You can write

$ python3 hello.py

where the source file name is given, or

$ python3 -m hello

where the module name (without extension .py) is given.

We will return to the use of command line arguments (sys.argv[]) when discussing the sys library.

Inside the Python shell

First start the Python shell from the operating system, then import the module from there.

$ python3

[welcome message displayed]

>>> import hello

You will then be able to execute statements that refer to functions and classes defined in hello.py:

>>> hello.hello()

Hello World

You can of course execute statements that do not refer to the imported module. This you can do even without importing any module:

$ python3

>>> print(2+2)

4

What is more, you can evaluate expressions in the shell, so that their values are shown, without the need of print() around.

>>> 2+2

4

This is a difference between writing code in the shell and in Python files: if you write just 2+2 on a line in a Python file, nothing is shown about it when you run the module. To see the value, you must make the expression into a statement by using print().

The shell has two kinds of prompts:

>>>, the primary prompt, corresponding to no indentation in a Python file,..., the secondary prompt, expecting added indentation.

The secondary prompt is needed when you for instance want to run a for loop in the shell:

>>> for i in range(2):

... print("Yes!")

...

Yes!

Yes!

You must remember to add the indentation and keep it constant. An empty line will get you back to level 0.

To my personal taste, it is quite awkward to write multiline statements in a shell, and therefore I prefer writing them inside functions in files and just calling these functions from the shell.

If you import hello from the Python shell, you can access the functions in it with the prefix hello..

You can avoid this by writing, instead,

>>> from hello import *

Then all names defined on the top level of the file become available without a prefix. This is handy if you open the file in the purpose of testing its functions in different combinations.

The effect of both ways of importing a module is that the statements in it are executed in the order in which they appear.

This can be disturbing, if you are for instance opening a module in order to test the functions in it one by one.

You can avoid most of the disturbance by not including print() statements on the top level but only inside functions - which is a good practice anyway.

A more general way to restrict the statements to use from command lines is to run them under the condition

if __name__ == '__main__':

# statements executed only when used from command line

3.3. Tutorial 3: An informal introduction to Python

Numbers

Here are some points of interest, potentially surprising:

- Integers have arbitrary size, whereas floats have limited precision. Therefore, int to float conversion can be lossy:

>>> int(float(12345678901234567890))

12345678901234567168

Notice that the type names int and float are themselves used as conversion functions.

- The floor division operator

//returns the largest integer smaller than the floating point value; its absolute value can be different depending on the sign of the result:

>>> 20 // 7

2

>>> -20 // 7

-3

Strings

Points of interest:

-

Single and double quotes mean the same; an advantage is that escapes of quotes are seldom needed:

'"Yes," they said.' -

Evaluating a string literal shows quotes (usually converted to single), printing it drops the quotes:

>>> 'hello' 'hello' >>> "hello" 'hello' >>> 'hello' == "hello" True >>> print('hello') hello -

Notice also that there is a type difference.

NoneTypeis used for expressions that return no useful value, such as those formed byprint(). To see the type, you can use thetype()function:>>> type('hello') <class 'str'> >>> type(print('hello')) hello <class 'NoneType'> -

Raw strings prefixed with

rtreat backslashes literally:>>> print('\tmp\name') mp ame >>> print(r'\tmp\name') \tmp\nameIn normal string literals,

\tis tab and\nis newline, as shown above. -

Triple quotes

"""enclose multiple line string literals. This is also the way to create multiline comments - or comment out blocks of code. -

Two or more string literals are glued together:

>>> 'Py' 'thon' 'Python' -

You can concatenate strings with

+and multiply by*:>>> name = 'Joe' >>> 'hey ' + name 'hey Joe' >>> 6*name 'JoeJoeJoeJoeJoeJoe' -

Notice that

print()takes many arguments, converts all to strings, and adds spaces:>>> print(name, 23, 'years') Joe 23 yearsBut

+requires explicit conversions and spaces:>>> name + 23 + 'years' TypeError: can only concatenate str (not "int") to str >>> name + str(23) + 'years' 'Joe23years' -

The index notation

[]returns characters in given positions, starting from 0. A negative index counts backwards from the last character, -1.>>> 'hello'[0] 'h' >>> 'hello'[4] 'o' >>> 'hello'[-1] 'o'Notice that there is no special type of characters: a character is simply a one-character string.

-

The slice notation generalizes from the index notation to substrings.

>>> 'hello'[1:4] 'ell'Notice that the first index is included, the second one is not: slices is like a semi-open intervals in mathematics, in this case

[1,4[. -

The start and end indices in slices are optional:

>>> 'hello'[:2] 'he' >>> 'hello'[2:] 'llo' -

Adding a third argument indicates a step

>>> '0123456789'[0:9:2] '02468'

Quiz: you can create the reverse of a string by using negative indices and steps. How?

The final point in this section is that strings are immutable. Mutability is a general topic, which we will cover when comparing strings with lists.

Lists

Points of interest:

-

Lists can be given with the bracket notation, and indexed and sliced just like strings:

>>> digits = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9] >>> digits[6] 6 >>> digits[3:6] [3, 4, 5] -

One can assign values to indices, as lists are mutable

>>> digits[4] = 'four' >>> digits [0, 1, 2, 3, 'four', 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]Notice here also that a list can contain elements of different types.

-

You can also assign lists to slices - even lists of a different size:

>>> digits[3:5] = ['III','IV'] >>> digits [0, 1, 2, 'III', 'IV', 5, 6, 7, 8, 9] >>> digits[3:5] = [] >>> digits [0, 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9] -

Unlike lists, strings are not mutable. To create a “mutable string”, you can make a copy that is converted to a list, and join the result back to a string:

>>> s = 'python' >>> ls = list(s) >>> ls ['p', 'y', 't', 'h', 'o', 'n'] >>> ls[0] = 'P' >>> ls ['P', 'y', 't', 'h', 'o', 'n'] >>> ''.join(ls) 'Python'

This is a useful technique when lots of changes are performed on a long string, because using lists instead of strings avoids creating new copies of the string.

First steps towards programming

The Fibonacci example

a, b = 0, 1

while a < 10:

print(a)

a, b = b, a+b

shows a while loop, which is probably familiar, but also two examples of a multiple assignment - assignment to several variables simultaneously.

A simple standard example of multiple assignment is swapping the values of two variables:

a, b = b, a

Without multiple assignments, doing this would require a temporary third variable.

3.4. Tutorial 4: More control flow tools

Loops and conditionals

Many of the statement forms for control flow are familiar from other languages, with just minor differences:

whileloops (above, from Tutorial 3.2),if-elif-elsestatements, which can have any number ofelifbranches,forloops, which can iterate over any iterable type (such lists and strings, but dictionaries and sets),breakstatements, which interrupt a loop and go back to the previous block level,continuestatements, which interrupt a loop and go to the next round of iteration,returnstatements anywhere in a function body terminates the execution of the function and returns the value of the expression given in the statements, orNoneif no expression is included.

Some statement forms are less familiar:

passstatements, which do nothing - commonly used as place-holders for what would be an empty block in a language using brackets,matchstatements, starting from Python 3.10, which enable structural pattern matching familiar from functional languages such as Haskell.

Of the familiar statements, for loops provide a prime example of what is considered “Pythonic”, that is, coding style that maximally uses the possibilities of Python.

Here is an example: a for loop that simply prints each character of a string:

for c in s:

print(c)

A less Pythonic way go get the same output is to loop over an index that ranges from 0 to the length of the string:

for i in range(len(s))

print(s[i])

This style is considered overly complicated, except if you really need to access the integer index. An example of this is if you want to print every second letter of a string:

for i in range(len(s))

if i%2 == 0:

print(s[i])

The range() function, by the way, creates sequences of integers,

- the sequence 0,1,2,3,4 for

range(5) - the sequence 2,3,4 for

range(2,5)

The function len() returns the length of a list or a string.

Another example where looping over an index is needed is the following: if you want to change a list, for instance increment each element in it by one, you might try

ds = [1, 2, 3, 4]

for d in ds:

d += 1

But this will not change the list ds.

What it does is just to give new values to the variable d.

The proper way to increment each element in the list is to assign to each element of it:

for i in range(len(ds)):

ds[i] += 1

One more thing: you might expect that the variable bound in the for loop has its scope limited to that loop.

But in fact, the variable continues to be alive, with the last value assigned to it in the loop.

Hence for instance i has the value 3 after the loop just shown.

This is different from many other programming languages, where variables declared in compound statements have their scopes only within those statements.

The match statement (Tutorial 4.6) is a novelty in Python 3.10.

It will look familiar to functional programmers - and it actually feels like the missing piece to some of us! - but we will cover it only later in these lecture notes, when we make sure that we have explained every detail of Python’s syntax.

Function definitions

Function definitions, as observed before, have no type information attached to the parameters or to the return values.

This makes it possible to define functions that return different types of values, or nothing at all (which in Python, however, is treated as value None), in different branches of a conditional.

An example is the following function that finds floating point roots for quadratic equations

import math

def quadratic_eq(a, b, c):

discr = b**2 - 4*a*c

if discr < 0:

print("no roots")

elif discr == 0:

return -b/(2*a)

else:

rdiscr = math.sqrt(discr)

return [(-b - rdiscr)/(2*a),

(-b + rdiscr)/(2*a)]

A problem with this style is that it is difficult for another function to take the output of this function as input. For instance, it cannot loop over the roots, because the result is iterable (a list) only if there are two roots. In this case, it would of course be easy to make each of the three branches return a list.

The number of arguments to a function can be varied by using optional arguments that have, if not given, default values:

def ask_ok(prompt, retries=4, reminder='Please try again!'):

The first argument is a positional arguments, which is compulsory to give. The other arguments can be given either by position or by using the variable name, then known as keyword arguments. The order of keyword arguments is not significant, but they must come after the positional arguments:

ask_ok('> ', 3) # third arg 'Please try again'

ask_ok('> ', reminder='Come on!') # second arg 4

ask_ok('> ', reminder='Come on!', retries=3)

Yet another specialty of Python is the use of packed arguments, marked by

*for any list (or tuple) of positional arguments,**for any list of keyword arguments

which must appear in this order, as in the Tutorial example

def cheeseshop(kind, *arguments, **keywords):

The markers / and * used as in

def f(pos1, pos2, /, pos_or_kwd, *, kwd1, kwd2):

are yet another way specify how arguments can be passed to a function. Tutorial Section 4.8.3.5 (in version 3.10) gives guidance for how to use this mechanism in the intended way.

Lambda expressions

Lambda expressions create anonymous functions - functions that are created without defining them with def statements.

A common use is in keyword arguments, for instance, in sorting:

>>> pairs = [(1, 'one'), (2, 'two'), (3, 'three'), (4, 'four')]

>>> pairs.sort(key=lambda pair: pair[1])

>>> pairs

[(4, 'four'), (1, 'one'), (3, 'three'), (2, 'two')]

An alternative to this would be:

def snd(pair):

return pair[1]

pairs.sort(key=snd)

The point with using lambda is that a line of code is saved and no name is needed for this function that is used only once. A limitation is that the definition of the lambda function must be single expression, hence it cannot contain statements.

Documentation strings and function annotations

A string literal immediately after a function header (the def line), as in:

def quadratic_eq(a, b, c):

"solving quadratic equations"

# etc

has a special status as a documentation string.

It gives the value of the “invisible” __doc__ variable, but also the answer to the help() function:

>>> quadratic_eq.__doc__

'solving quadratic equations'

>>> help(quadratic_eq)

Help on function quadratic_eq in module mymath:

quadratic_eq(a, b, c)

solving quadratic equations

Including documentation strings is a good practice, in particular in library functions. They can consist of many lines if triple quotes are used.

Functions can also be equipped with annotations (Tutorial 4.8.8) that give type information. They can be useful for documentation, but, unlike in e.g. Java, they are not checked by the compiler, and their expressivity is limited. For example, if a function has variable argument and return types, there is no standard way to express this.

Coding style

We have already mentioned then “Pythonic” recommendations to use 4 spaces for indentation 2 empty lines between functions, and maximum line length 79 characters. Some others are mentioned here, and we will try to follow them, in particular:

- spaces after commas, e.g.

f(x, y), lowercase_with_underscoresfor function names.

In many other languages, camelCase is preferred for function names, which makes it natural to continue this convention in Python.

However, this will soon lead to mixtures of the two conventions when libraries are used, which gives a messy impression.

3.5. Tutorial 5: Data structures

This section covers different types of collections:

- lists, e.g.

[1, 4, 9] - dictionaries, e.g.

{'computer': 'dator', 'language': 'språk'} - tuples, e.g.

'computer', 'dator'(parentheses not needed!) - sets, e.g.

{1, 4, 9}

To these, one could also add two kinds of sequences that we have already seen:

- strings, e.g.

hello - ranges, e.g.

range(1,101)

These six types have a lot in common, but also differences that make them usable for different purposes. Therefore it is often necessary to convert between them, and we will cover some of the main ways to do so. The conversions sometimes work as expected, but sometimes lead to loss of information. Thus converting a list of tuples into a dictionary keeps both components of tuples, but converting a dictionary into a list only keeps the keys:

>>> dict([(1, 2)])

{1: 2}

>>> list({1: 2})

[1]

Notice, however, that converting a list with several values given to the same keys results in a dictionary that only includes the last of the values:

>>> dict([(1, 2), (1, 5)])

{1: 5}

The fundamental explanation of all differences lies in a handful of hidden methods in class definitions, which we will cover in the chapter on the data model of Python. The visible part of these concepts can be seen in type error messages, such as:

>>> s = "hello"

>>> s[3] = 'c'

TypeError: 'str' object does not support item assignment

You should go through all of the methods listed in the official Tutorial 5.1, not only for lists but also for the other data structures, to get a feeling of which of them work for which.

Notice that all of the collections mentioned in this section are objects of classes, which have methods applied by using a special syntax - for instance,

xs.sort()

which is really a shorthand for a function application

list.sort(xs)

In other words, the object xs is really the first argument of the function sort()from the class list.

Normally, the first variant, the object-oriented notation is recommended for these functions.

Comprehensions

List comprehensions are introduced in the official tutorial 5.1.3, and provide a powerful, highly Pythonic way to create lists from given ones via the operations of mapping and filtering.

Mapping is the transformation of every item in a list in a certain way, for example squaring a list of numbers. This can be done using a simple for loop:

numbers = [1,2,3,4,5]

squares = []

for n in numbers:

squares.append(n**2)

Using a list comprehension this can be expressed as:

>>> [ n**2 for n in numbers ]

[1, 4, 9, 16, 25]

Filtering is selecting a subset of items from a list based on some predicate, for example filtering out the even numbers:

evens = []

for n in numbers:

if n % 2 == 0:

evens.append(n)

Using a list comprehension this can be expressed as:

>>> [ n for n in numbers if n % 2 == 0 ]

[2, 4]

Furthermore, list comprehensions allow us to map and filter together, for example building a list of squares of even numbers:

>>> [ n**2 for n in numbers if n % 2 == 0 ]

[4, 16]

What gives even more power is that comprehensions work for other collection types as well, and even for mixtures of them. Thus we have dictionary comprehensions,

>>> {n: n**3 for n in range(7)}

{0: 0, 1: 1, 2: 8, 3: 27, 4: 64, 5: 125, 6: 216, 7: 343}

and set comprehensions

>>> {n % 3 for n in range(100)}

{0, 1, 2}

We will make heavy use of comprehensions as a query language for structured data in Chapter 4.

Booleans

There are a couple of special things about booleans:

-

Keywords

and,or,notare used for boolean operators. -

Comparison operators can be chained:

a < b <= cmeans the same asa < b and b <= c. -

Many types can be cast into booleans:

0,'',[],{}all count asFalsewhen used in conditions. -

Boolean

orcan return values in these other types:>>> {} or 0 or 'this' 'this' >>> {} or 0 0 -

Finally, let us tell you a secret that is not covered by the tutorial: Python has a conditional expressions, which have a slightly surprising syntax:

>>> x = 10 >>> 'big' if x > 10 else 'small' 'small'Thus the “true” value comes first, the condition in the middle, and the “false” value last.

A summary of collection types

| type | notation | indexing | assignment | mutable | order | reps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

str |

'hello' |

s[2] |

- | no | yes | yes |

list |

[1, 2, 1] |

l[2] |

l[2] = 8 |

yes | yes | yes |

tuple |

(1, 2, 1) |

t[2] |

- | no | yes | yes |

dict |

{'x': 12} |

d['x'] |

d['x'] = 9 |

yes | no | no |

set |

{1, 2} |

- | - | yes | no | no |

range |

range(1,7) |

r[2] |

- | no | yes | no |

The difference between lists and sets is the familiar one from mathematics: lists care about the order of elements, and remember repetitions of elements (“reps” in the table), whereas sets store every element just ones and does not specify their order. Hence the order in which a set is converted to a list can be different from the order in which the set was defined:

>>> s = {4, 1, 2}

>>> list(s)

[1, 2, 4]

This also explains why indexing with position does not work for sets.

Dictionaries function as sets in two respects: order and repetitions. But unlike sets, they allow indexing via keys (the things on the left sides of the colons).

The ordering is illustrated by how equality works. The following tests show that order matters for lists but not for sets:

>>> [2, 3] == [3, 2]

False

>>> {2, 3} == {3, 2}

True

What about dictionaries? A new implementation in Python 3.6 is reported to preserve the order in which the items are introduced; see https://docs.python.org/3.6/whatsnew/3.6.html.

However, this does not change the mathematical property that order is irrelevant (tested in 3.9.7):

>>> {1: 2, 2: 3} == {2: 3, 1: 2}

True

Mutability and item assignment go hand in hand, except for sets, where indexing makes no sense.

But sets are still mutable, by the add() and remove() methods:

>>> s = {4, 1, 2}

>>> s.add(8)

>>> s

{8, 1, 2, 4}

>>> s.remove(2)

>>> s

{8, 1, 4}

3.6. Tutorial 6: Modules

3.6.1. Importing

Modules can be imported from both the Python shell and from Python files in many different ways:

-

import mathmakesmath.cos(), math.sin()available -

import math as mmakesm.cos(), m.sin()available -

from math import cosmakescos()available (but notsin()) -

from math import cos, sinmakescos(), sin()available -

from math import *makescos(), sin(), tan(),… available

The last way of importing everything from a module without a prefix may be tempting, since it saves typing, but it also opens the way for hard to detect name clashes when the same names are used in other modules that are in scope. It is mainly used in the Python shell when testing the functions of your own modules that are under development.

3.6.2. Running a main function

When a Python file is executed from the operating system or imported in the Python shell, all its top-level statements (i.e. ones not enclosed in functions or classes) are executed, e.g. all print statements.

But nothing else is executed - in particular, function definitions.

Hence, even if a function has the name main(), it is not executed, if it is only defined but not called.

Calling main(), however, is not always desirable either.

Hence the common idiom is to call it conditionally.

The condition is that the module is executed as a main module, e.g. from the operating system shell.

Then Python gives the module the name __main__, and the conditional call can be written

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Now, since the function name main has no special status, you can often see code where the same condition is prefixed to other kinds of code.

This is of course fine - but it can still add clarity to the code if there is a function that has the name main and is used in the way specified.

3.6.3. Listing names with dir()

The built-in function dir() shows the names currently in scope

dir(m)lists names in modulem,dir()lists the names you have defined in the current session.

So it is a good way quickly to look up names.

As we have seen, help() can then give more information about a name, especially if it has been given a document string.

3.6.4. The rest of Tutorial 6

There are some more details about

- the module search path,

- compilation to

.pycfiles, - the

sysmodule, - packages

But we will save these details to later occasions, where we will need them.

3.7. Tutorial 7: Input and Output

3.7.1. String formatting

Assume you want to report the populations of countries, e.g.

country = 'Sweden'

population = 10_402_070

(yes, you can group digits in number literals with underscores!) The string you want to produce is

'the population of Sweden is 10402070'

This string can be produced in many ways:

-

by using

+between the parts, converted to strings if necessary:'the population of ' + country + ' is ' + str(population) -

with an f-string (string prefixed with

f):f'the population of {country} is {population}' -

with the

format()method:'the population of {} is {}'.format(country, population) -

with the

%operator (“printf-style”, inspired by the C language):'the population of %(c)s is %(p)d' % {'c': country, 'p': population}

The printf-style % operator is considered deprecated, but it is common in older Python code, so one has to be able to read it.

It has a wide range of options about argument types and rounding.

F-strings are the most recent method and recommended since Python 3.6.

Both f-strings and the format() method provide a wide range of possibilities, described in:

https://docs.python.org/3/library/string.html#formatstrings

What can be included in the {} parts is therefore called a “Mini-Language”.

There are some differences between how arguments are given to f-strings and the format() method.

One place to look is:

https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0498/

PEP, by the way, is a series of Python Enhancement Proposals, where each new feature of Python is discussed before it is released. It is the ultimate source of explanations and design choices of those features.

The formatting “mini-language” has its own syntax, which is more compressed and therefore often harder to read than normal Python syntax.

For example, argument types are one-letter symbols similar to the old printf style: d means decimal integers.

It can often be avoided by modifying the arguments themselves with usual Python operators.

Here is an example: we want to print the populations of many countries in a table of fixed-width columns, where the country names are left-justified and their populations right-justified:

Iceland 371580

Sweden 10402070

We can do this with the mini-language syntax, where justification is indicated by the < and > signs:

f'{country:<24} {population:>12}'

But we can also use the normal string methods ljust() and rjust():

f'{country.ljust(24)} {str(population).rjust(12)}'

The mini-language method is more compact, but needs the mastery of a new “language”, and is also harder to read for those who do not know the language. The normal method needs more writing, and can be harder to read just because the code becomes longer. But it gives the full power of Python’s string operations. The mini-language has more limited functionalities, but has on the other hand made some commonly used patterns readily available.

3.7.2. Reading and writing files

When you open a file in the reading mode, you get an iterator over the lines of the file.

You can then read the lines one by one with the next() function:

>>> countries = open('countries.tsv', 'r')

>>> next(countries)

'Afghanistan\t36643815\n'

>>> next(countries)

'Albania\t3020209\n'

The file is read lazily: its contents are not stored in the memory, but read one by one and then forgotten.

When you have reached the end of the file, next() gives an error.

You should always close a file when you do not need it any more:

countries.close()

A modern and recommended way is to read the file inside a with statement.

This is the syntax used for context managers, of which opening and closing files is an example.

Here is an example where each line of the file is printed as a formatted table:

with open('countries.tsv', 'r') as infile:

for line in infile:

data = line.split('\t')

country, population = data[0].strip(), data[1].strip()

print(f'{country:<24} {population:>12}')

Functions split() and strip() are standard methods of strings; if you don’t know them already, consult their standard documentation:

>>> help(str.split)

Now, the above code can give unwanted results because some country names are too long:

Saint Lucia 178844

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines 109897

Samoa 196440

To be certain to prevent this, you have to compute the maximum length of country names, which requires traversing the entire list before printing any output. We leave this as an exercise.

If you want to write into a file, one way is to redirect the output of program in the operating system call of Python:

$ python3 print_pop.py > formatted-countries.txt

From inside Python, you can do this by opening a file in the w mode,

with open('formatted-countries.txt', 'w') as outfile:

outfile.write(s) # a string that you have constructed

You can also combine reading a file and writing to another file:

with open('countries.tsv', 'r') as infile:

with open('formatted-countries.txt', 'w') as outfile:

for line in infile:

outfile.write(formatted(line))

Depending on what the formatted() function does, you may or may not need to add a newline too the end of every line you output.

3.7.3. The rest of Tutorial 7

-

some more methods on file objects: read if you need them

-

the JSON format: to be covered in more detail in Chapter 4 and used heavily throughout the course.

3.8. Tutorial 8: Errors and Exceptions

The internals of error handling presuppose knowledge of classes, so we leave them to Chapters 5 and 6. The most important features of error handling are given in an example in Standard Tutorial 8.7:

def divide(x, y):

try:

result = x / y

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("division by zero!")

else:

print("result is", result)

finally:

print("executing finally clause")

>>> divide(2, 1)

result is 2.0

executing finally clause

>>> divide(2, 0)

division by zero!

executing finally clause

>>> divide("2", "1")

executing finally clause

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 3, in divide

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for /: 'str' and 'str'

3.9. Tutorial 9: Classes

The topic of classes will be discussed more thoroughly in Chapter 6. Here we will just mention some highlights.

3.9.1. Namespaces and scopes

The Tutorial chapter 9 starts with a discussion of namespaces, which are mappings of names (variables, functions, classes, modules) to objects.

Namespaces are a feature of the runtime state of the program built in the computer’s memory.

In the source code, the related term scope means a part of the code where a name space is directly accessible, i.e. names can be used without qualifiers (e.g. pi instead of math.pi).

There is an unlimited hierarchy of namespaces and scopes. In an order opposite to the list in Tutorial 9.2, we have

- built-in names

- names in the current module (functions, classes, global variables)

- names in the current function (parameters and other local variables)

- names in function inside that function

- and so on, because functions can be nested

The notions of global and non-local variable are a bit tricky, in particular since the status can be modified by keywords. The code example in 9.2.1 is worth studying: the effect “After global assignment” can be surprising.

3.9.2. Class definitions

The format of class definitions is extremely liberal: it can consist of any statements, including just pass.

class <name>:

<statements>

These statements define their own namespace, outside which the names must be qualified by the class name. These names are called attributes.

New instances of the class are created by using the class name as a function:

<classname>()

The instances can introduce their own attributes: there is no requirement that all instances of a class have the same attributes. This makes classes extremely flexible in Python.

However, there is a more restricted way to use classes, which is closer to the usual ideas of object-oriented design. Here is an example from two-dimensional graphics, with a typical structure and some terminology:

class Point:

"points in a two-dimensional space"

# creating a point

def __init__(self, x, y):

"create a point by giving x and y coordinates"

# the instance variables _x and _y are "private"

self._x = x

self._y = y

# public getters of the two coordinates

def get_x(self):

return self._x

def get_y(self):

return self._x

# public setters of the two coordinates

def set_x(self, x):

self._x = x

def set_y(self, y):

self._y = y

# any number of other methods

def move(self, dx, dy):

self.set_x(self.get_x() + dx)

self.set_y(self.get_y() + dy)

A class can extend other classes and thereby inherit its attributes:

class ColoredPoint(Point):

def __init__(self, x, y, color='black'):

"give coordinates, and optionally color, default black"

super().__init__(x, y)

self._color = color

def get_color(self):

return self._color

def set_color(self, color):

self._color = color

The following session shows how instances can be created and accessed:

>>> p = ColoredPoint(3, 5)

>>> p.get_x()

3

>>> p.move(1, 10)

>>> p.get_x()

4

>>> p.get_color()

'black'

>>> p.set_color('red')

>>> p.get_color()

'red'

3.10. Tutorial 10 and 11: the Standard Library

In the labs and exercises of this course, we will need at least the following standard libraries and functions:

-

sys, system:argvcommand line arguments -

re, regular expressions: methods for analysing strings -

math, mathematical functions:sin(),cos(),pi -

random:choice(),randrange() -

statistics:mean(),median() -

urllib, accessing the internet:urlopen() -

timeit, measuring the time to perform a computation:timeit() -

collections:deque() -

json, to structure and store data in files -

csv, to read and write files with comma-separated data (or with some other delimiter such as tab) -

xml.etree.ElementTree, to read and write XML data -

ast, Abstract Syntax Trees, to analyse Python code

We will also use libraries from other sources.

Those will probably need to be installed with the pip program, for instance,

$ pip3 install graphviz

for the library we will use for the visualization of graphs.

3.11. Tutorial 12: Packages and virtual environments

Package management

When programming, we often want to install external packages which are not part of the standard library.

The Python Package Index (pypi) is a repository of publicly-published packages by the Python community.

Python comes with a package manager called pip, and in the simplest case you can install a new package named foo with a command like:

$ pip3 install foo

What this command does search for a package with the name foo, and if found installs the latest version of it.

That’s all well and good, but what if another Python project you are working on requires a different version of the foo package?

Packages are being updated all the time, and so are the dependencies between them.

Often you can’t just always install the latest version of everything, but instead rely on fixed versions which you know work.

Some recent versions of Python will even warn you about trying to install packages globally, and refuse to do so unless you explicitly override it.

Virtual environments

To avoid the packages from one project interfering with one another, it is recommended to create a virtual environment for each Python project that you work on. Packages are then installed into this virtual environment, rather than globally, to minimise the chance of different versions conflicting with eachother.

The module used to create and manage virtual environments is called venv.

To create a virtual environment, decide upon a directory where you want to place it.

A common name for this directory is .venv, but it could be anything you want.

Then run the venv module as a script with the directory path as argument:

$ python3 -m venv .venv

You will now see a new folder called .venv which contains the files for your virtual environment.

To make sure that you are operating inside this virtual environment in your shell, you need to activate it:

-

On macOS or Linux:

$ source venv/bin/activate -

Windows Command Shell (

cmd):$ venv/Scripts/activate.bat -

Windows PowerShell:

$ venv/Scripts/activate.ps1

You should now see that your shell prompt is prefixed by the name of the virtual environment:

(.venv) $

VS Code will usually detect that a virtual environment has been created and asks if you want to use it, choose yes!

3.12. Tutorial 13: What Now?

The most thorough and widely usable documents are

-

the Python Language Reference: https://docs.python.org/3/reference/index.html#reference-index

-

the Python Standard Library: https://docs.python.org/3/library/index.html#library-index

4. Storing and retrieving information

This chapter (with its pointers and your own practice) makes you ready to start with Lab 1.

4.1. Databases

A database is an integral part of many software systems. In general terms, it is a collection of data which is not a part of the program code, but resides in separate files or even on different servers around the Internet.

A programming language like Python would of course be able to express a database as a part of program code, by using dictionaries and lists. But this is normally not done. Instead, Python provides functions for retrieving data from a database, storing new data, and updating old data. Dictionaries and lists are used at runtime when the data is processed. The files can use textual formats such as JSON, CSV, and TSV, which are in focus in this chapter. In large databases, compressed binary data is common, but outside our focus.

In this chapter, we will look at two kinds of data: tabular and hierarchic (tree-like). We will look at how data is stored in files and how it is used in Python. Both of these tasks will then be trained in Lab 1. The lab will moreover emphasize a fundamental principle of database design: avoiding redundancy - one should “say each thing only once.”

One aspect of databases that we do not address here is persistent storage. We will just read the database from file to memory and manipulate it in memory, as a Python object. The data becomes persistent when we write it back to a file, but there is no guarantee of persistence at the intermediate stages: if the computer is turned off before saving to a file, the data is lost.

4.2. Tabular data

A simple example of a database is a table, which consists of a number of rows that contain pieces of information in different columns. Such a table can be stored as a text file, where each line contains a row, and the columns are separated by a delimiter such as a comma or a tabulator. Spreadsheet programs such as Excel can both read and write tables in such formats; Excel is indeed perhaps the most widely used technology for tabular databases, although not officially recognized as databases. A more advanced technology is relational databases, also known as SQL databases. While Python - no surprise! - has libraries that support Excel and SQL as well, they are beyond the scope of this course.

4.2.1. Reading tabular data from files

Here is an example: the beginning of a table with information about the countries of the world:

| country | capital | area | population | continent | currency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | Kabul | 652230 | 36643815 | Asia | afghani |

| Albania | Tirana | 28748 | 3020209 | Europe | lek |

| Algeria | Algiers | 2381741 | 41318142 | Africa | dinar |

| Andorra | Andorra la Vella | 468 | 76177 | Europe | euro |

The data could be stored in a CSV file (Comma-Separated Values), which uses the comma as delimiter,

Afghanistan,Kabul,652230,36643815,Asia,afghani

or a TSV file (Tab-Separated Values), which uses the tabulator \t,

Afghanistan\tKabul\t652230\t36643815\tAsia\tafghani

A complete such file can be found in countries.tsv which contains the data referred to in this chapter.

Files of these forms can correspondingly be read into Python by using the split() method: for CSV,

with open('FILE.csv') as file:

data = []

for line in file:

data.append(line.split(','))

This simple piece of code is, however, too brittle.

Special attention must be paid to situations where some field itself contains the delimiter character or a newline.

The Python standard library csv (documentation: https://docs.python.org/3/library/csv.html)

provides functions for dealing with such situations, with freely chosen delimiters (comma is just the default) and “dialects” such as Excel.

Here is how to read a TSV file:

import csv

with open('FILE.tsv') as file:

rows = csv.reader(file, delimiter='\t')

data = [row for row in rows]

4.2.2. Processing tabular data in Python

Reading a file, either with the the above split() method or with the csv library, results in a list of lists of strings, such as

[

['country', 'capital', 'area', 'population', 'continent', 'currency'],

['Afghanistan', 'Kabul', '652230', '36643815', 'Asia', 'afghani'],

['Albania', 'Tirana', '28748', '3020209', 'Europe', 'lek'],

['Algeria', 'Algiers', '2381741', '41318142', 'Africa', 'dinar']

]

The first line is used as the header that gives the labels, also known as attributes, of each column. A simple conversion (left as exercise!) converts this to a list of dictionaries, where the keys are these labels, repeated for every row of data:

[

{'country': 'Afghanistan', 'capital': 'Kabul', 'area': '652230',

'population': '36643815', 'continent': 'Asia', 'currency': 'afghani'},

{'country': 'Albania', 'capital': 'Tirana', 'area': '28748',

'population': '3020209', 'continent': 'Europe', 'currency': 'lek'},

{'country': 'Algeria', 'capital': 'Algiers', 'area': '2381741',

'population': '41318142', 'continent': 'Africa', 'currency': 'dinar'}

]

In many applications, it is more practical to use the country names as keys. For this purpose, one can convert this list into a dictionary of dictionaries:

{

'Afghanistan': {'capital': 'Kabul', 'area': 652230, 'population': 36643815, 'continent': 'Asia', 'currency': 'afghani'},

'Albania': {'capital': 'Tirana', 'area': 28748, 'population': 3020209, 'continent': 'Europe', 'currency': 'lek'},

'Algeria': {'capital': 'Algiers', 'area': 2381741, 'population': 41318142, 'continent': 'Africa', 'currency': 'dinar'}

}

Notice that we have now converted numerical values from strings to integers. Producing this format is also left as an exercise. The last resulting dictionary is perhaps the most natural form for a database of countries. Having country names as dictionary keys makes it fast to look up information about each country.

>>> cdict['Sweden']['population']

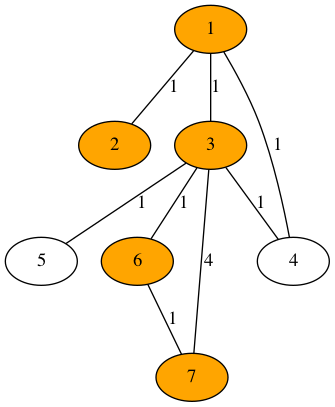

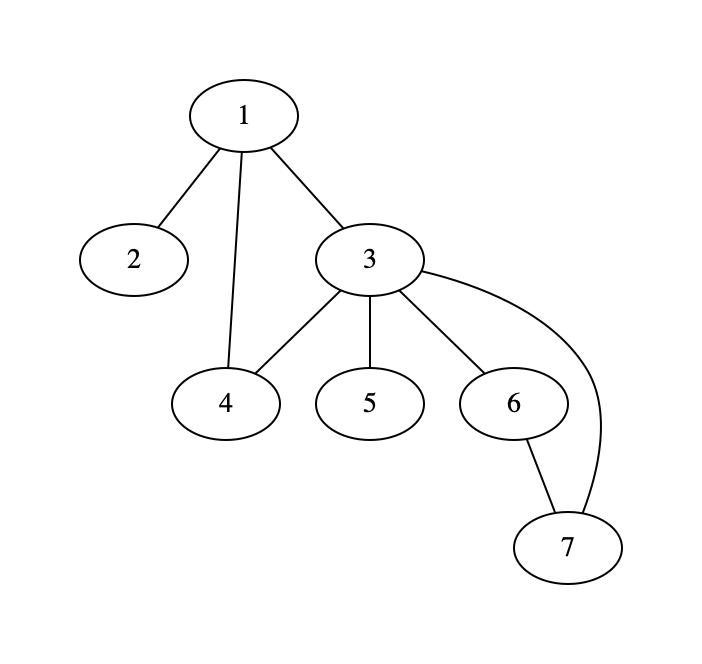

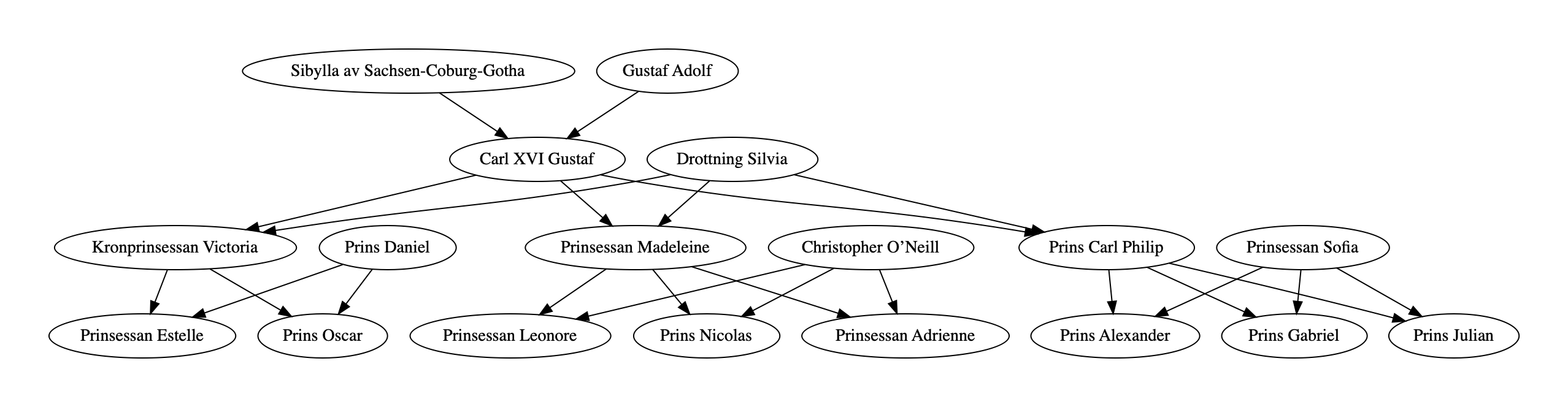

10379295